MEMORANDUM OF AGREEMENT

KNOW ALL MEN BY THESE PRESENTS:

This Memorandum of Agreement is entered into by and among the Send a Soul to School (SSoS) Movement, Jagna Chapter, Jagna, Bohol, herein represented by Fr. Jose Conrado A. Estafia, herein referred to as the First Party and ____________________________________, the selected scholar of the First Party for the course of ____________________________________ at the (school)________________________________________________, (address of school)_______________________________________, herein to as the Second Party and _________________________________________________, parents (if none, guardians) of the Second Party.

WITNESSETH

Whereas, SSoS was established by its members for the purpose of helping deserving indigent students to complete a college or vocational course they are capable of as well as to give spiritual and value formations to scholars and their families and to donors and members of the movement;

Whereas, to ensure successful implementation of this program, hereunder are the duties and responsibilities of each parties which they agree voluntarily;

FOR THE SCHOLARS

1. Submit complete requirements;

2. Submit study load after the enrolment and a copy of the course curriculum as needed;

3. Attend any required recollection, value formation seminars and trainings;

4. Actively participate in any church-related activities especially during vacation time as required by the movement;

5. Support the SSoS movement after graduation and having found employment by becoming the future donors and contribute a minimum of OneThousand Pesos (P 1, 000.00) per semester;

6. Refund the movement of all expenses made if the scholar fails to finish his/her course without valid reason;

7. The scholar is expected to get an average grade of at least 85 or its equivalent grading system of all subjects enrolled per semester or not less than 80 or its equivalent per subject. Failure to comply will be subjected to the movement’s evaluation;

8. Any failing grade shall automatically dismiss the scholar from the program;

9. Strictly no withdrawal of subjects;

10. The scholar is allowed to enroll in one (1) course only and shifting to another course is not allowed.

FOR THE PARENTS OF THE SCHOLARS

1. To actively participate in any religious and socio-cultural activities as required by the movement;

2. To constantly support and follow-up their children;

3. To attend Sunday masses, join religious organizations and actively participate in any recollection and value formation seminars and trainings organized by the movement;

4. Shoulder other expenses and payments of the scholar not included in the program.

RESPONSIBILITIES OF THE SSoS MOVEMENT

1. Shoulders and pays the tuition fees, laboratory fees, registration, miscellaneous fees which includes library, medical/dental, athletics, guidance and testing, audio/visual, exam supplies, student development/human resource development (counseling, training), cultural fees, publications, modernization/upgrading for the school amenities. The movement also shoulders the following: board and lodging fees, living allowance, books (only required textbooks), provision for uniforms, retreats, field trips (half amount only), review and board examination fees.

2. The following fees are excluded from the movement’s responsibility: school activities (parties, outings, acquaintance), school projects, graduation fees, graduation related expenses including diploma fees, thesis materials and oral defense (if any), alumni membership fees, homecoming assessment, toga, yearbook, class ring and such related expenses not hereto identified.

IN WITNESS WHEREOF, the parties hereunto affix their signatures this ___________ day of _________________, 2007 at Jagna, Bohol, Philippines.

___________________________

Name of Scholar

___________________________

Parents

Fr. Jose Conrado A. Estafia

SSoS Founder

Saturday, June 23, 2007

Thursday, May 10, 2007

Why are Filipinos so Poor? by F. Sionil Jose

In the ’50s and ’60s, the Philippines was the most envied country in Southeast Asia. What happened?

What did South Korea look like after the Korean War in 1953? Battered, poor - but look at Korea now. In the Fifties, the traffic in Taipei was composed of bicycles and army trucks, the streets flanked by tile-roofed low buildings. Jakarta was a giant village and Kuala Lumpur a small village surrounded by jungle and rubber plantations. Bangkok was criss-crossed with canals, the tallest structure was the Wat Arun, the Temple of the Sun, and it dominated the city’s skyline. Ricefields all the way from Don Muang airport — then a huddle of galvanized iron-roofed bodegas, to the Victory monument.Visit these cities today and weep — for they are more beautiful, cleaner and prosperous than Manila. In the Fifties and Sixties we were the most envied country in Southeast Asia. Remember further that when Indonesia got its independence in 1949, it had only 114 university graduates compared with the hundreds of Ph.D.’s that were already in our universities. Why then were we left behind? The economic explanation is simple. We did not produce cheaper and better products.

The basic question really is why we did not modernize fast enough and thereby doomed our people to poverty. This is the harsh truth about us today. Just consider these: some 15 years ago a survey showed that half of all grade school pupils dropped out after grade 5 because they had no money to continue schooling.Thousands of young adults today are therefore unable to find jobs. Our natural resources have been ravaged and they are not renewable. Our tremendous population increase eats up all of our economic gains. There is hunger in this country now; our poorest eat only once a day.But this physical poverty is really not as serious as the greater poverty that afflicts us and this is the poverty of the spirit.

Why then are we poor? More than ten years ago, James Fallows, editor of the Atlantic Monthly, came to the Philippines and wrote about our damaged culture which, he asserted, impeded our development. Many disagreed with him but I do find a great deal of truth in his analysis.This is not to say that I blame our social and moral malaise on colonialism alone. But we did inherit from Spain a social system and an elite that, on purpose, exploited the masses. Then, too, in the Iberian peninsula, to work with one’s hands is frowned upon and we inherited that vice as well. Colonialism by foreigners may no longer be what it was, but we are now a colony of our own elite.

We are poor because we are poor — this is not a tautology. The culture of poverty is self-perpetuating. We are poor because our people are lazy. I pass by a slum area every morning - dozens of adults do nothing but idle, gossip and drink. We do not save. Look at the Japanese and how they save in spite of the fact that the interest given them by their banks is so little. They work very hard too.

We are great show-offs. Look at our women, how overdressed, over-coiffed they are, and Imelda epitomizes that extravagance. Look at our men, their manicured nails, their personal jewelry, their diamond rings. Yabang - that is what we are, and all that money expended on status symbols, on yabang. How much better if it were channeled into production.

We are poor because our nationalism is inward looking. Under its guise we protect inefficient industries and monopolies. We did not pursue agrarian reform like Japan and Taiwan. It is not so much the development of the rural sector, making it productive and a good market as well. Agrarian reform releases the energies of the landlords who, before the reform, merely waited for the harvest. They become entrepreneurs, the harbingers of change.

Our nationalist icons like Claro M. Recto and Lorenzo Tanada opposed agrarian reform, the single most important factor that would have altered the rural areas and lifted the peasant from poverty. Both of them were merely anti-American.

And finally, we are poor because we have lost our ethical moorings. We condone cronyism and corruption and we don’t ostracize or punish the crooks in our midst. Both cronyism and corruption are wasteful but we allow their practice because our loyalty is to family or friend, not to the larger good.

We can tackle our poverty in two very distinct ways. The first choice: a nationalist revolution, a continuation of the revolution in 1896. But even before we can use violence to change inequities in our society, we must first have a profound change in our way of thinking, in our culture. My regret about EDSA is that change would have been possible then with a minimum of bloodshed. In fact, a revolution may not be bloody at all if something like EDSA would present itself again. Or a dictator unlike Marcos.

The second is through education, perhaps a longer and more complex process. The only problem is that it may take so long and by the time conditions have changed, we may be back where we were, caught up with this tremendous population explosion which the Catholic Church exacerbates in its conformity with doctrinal purity.We are faced with a growing compulsion to violence, but even if the communists won, they will rule as badly because they will be hostage to the same obstructions in our culture, the barkada, the vaulting egos that sundered the revolution in 1896, the Huk revolt in 1949-53.

To repeat, neither education nor revolution can succeed if we do not internalize new attitudes, new ways of thinking. Let us go back to basics and remember those American slogans: A Ford in every garage. A chicken in every pot. Money is like fertilizer: to do any good it must be spread around.Some Filipinos, taunted wherever they are, are shamed to admit they are Filipinos. I have, myself, been embarrassed to explain, for instance, why Imelda, her children and the Marcos cronies are back, and in positions of power. Are there redeeming features in our country that we can be proud of? Of course, lots of them. When people say, for instance, that our corruption will never be banished, just remember that Arsenio Lacson as mayor of Manila and Ramon Magsaysay as president brought a clean government.We do not have the classical arts that brought Hinduism and Buddhism to continental and archipelagic Southeast Asia, but our artists have now ranged the world, showing what we have done with Western art forms, enriched with our own ethnic traditions. Our professionals, not just our domestics, are all over, showing how accomplished a people we are!

Look at our history. We are the first in Asia to rise against Western colonialism, the first to establish a republic. Recall the Battle of Tirad Pass and glory in the heroism of Gregorio del Pilar and the 48 Filipinos who died but stopped the Texas Rangers from capturing the president of that First Republic. Its equivalent in ancient history is the Battle of Thermopylae where the Spartans and their king Leonidas, died to a man, defending the pass against the invading Persians. Rizal — what nation on earth has produced a man like him? At 35, he was a novelist, a poet, an anthropologist, a sculptor, a medical doctor, a teacher and martyr.We are now 80 million and in another two decades we will pass the 100 million mark.

Eighty million — that is a mass market in any language, a mass market that should absorb our increased production in goods and services - a mass market which any entrepreneur can hope to exploit, like the proverbial oil for the lamps of China.

Japan was only 70 million when it had confidence enough and the wherewithal to challenge the United States and almost won. It is the same confidence that enabled Japan to flourish from the rubble of defeat in World War II.

I am not looking for a foreign power for us to challenge. But we have a real and insidious enemy that we must vanquish, and this enemy is worse than the intransigence of any foreign power. We are our own enemy. And we must have the courage, the will, to change ourselves.

F. Sionil Jose, whose works have been published in 24 languages, is also a bookseller, editor, publisher and founding president of the the PhilippinesÕ PEN Center. The foregoing is an excerpt from a speech delivered by Mr. Jose in Manila, Philippines.

What did South Korea look like after the Korean War in 1953? Battered, poor - but look at Korea now. In the Fifties, the traffic in Taipei was composed of bicycles and army trucks, the streets flanked by tile-roofed low buildings. Jakarta was a giant village and Kuala Lumpur a small village surrounded by jungle and rubber plantations. Bangkok was criss-crossed with canals, the tallest structure was the Wat Arun, the Temple of the Sun, and it dominated the city’s skyline. Ricefields all the way from Don Muang airport — then a huddle of galvanized iron-roofed bodegas, to the Victory monument.Visit these cities today and weep — for they are more beautiful, cleaner and prosperous than Manila. In the Fifties and Sixties we were the most envied country in Southeast Asia. Remember further that when Indonesia got its independence in 1949, it had only 114 university graduates compared with the hundreds of Ph.D.’s that were already in our universities. Why then were we left behind? The economic explanation is simple. We did not produce cheaper and better products.

The basic question really is why we did not modernize fast enough and thereby doomed our people to poverty. This is the harsh truth about us today. Just consider these: some 15 years ago a survey showed that half of all grade school pupils dropped out after grade 5 because they had no money to continue schooling.Thousands of young adults today are therefore unable to find jobs. Our natural resources have been ravaged and they are not renewable. Our tremendous population increase eats up all of our economic gains. There is hunger in this country now; our poorest eat only once a day.But this physical poverty is really not as serious as the greater poverty that afflicts us and this is the poverty of the spirit.

Why then are we poor? More than ten years ago, James Fallows, editor of the Atlantic Monthly, came to the Philippines and wrote about our damaged culture which, he asserted, impeded our development. Many disagreed with him but I do find a great deal of truth in his analysis.This is not to say that I blame our social and moral malaise on colonialism alone. But we did inherit from Spain a social system and an elite that, on purpose, exploited the masses. Then, too, in the Iberian peninsula, to work with one’s hands is frowned upon and we inherited that vice as well. Colonialism by foreigners may no longer be what it was, but we are now a colony of our own elite.

We are poor because we are poor — this is not a tautology. The culture of poverty is self-perpetuating. We are poor because our people are lazy. I pass by a slum area every morning - dozens of adults do nothing but idle, gossip and drink. We do not save. Look at the Japanese and how they save in spite of the fact that the interest given them by their banks is so little. They work very hard too.

We are great show-offs. Look at our women, how overdressed, over-coiffed they are, and Imelda epitomizes that extravagance. Look at our men, their manicured nails, their personal jewelry, their diamond rings. Yabang - that is what we are, and all that money expended on status symbols, on yabang. How much better if it were channeled into production.

We are poor because our nationalism is inward looking. Under its guise we protect inefficient industries and monopolies. We did not pursue agrarian reform like Japan and Taiwan. It is not so much the development of the rural sector, making it productive and a good market as well. Agrarian reform releases the energies of the landlords who, before the reform, merely waited for the harvest. They become entrepreneurs, the harbingers of change.

Our nationalist icons like Claro M. Recto and Lorenzo Tanada opposed agrarian reform, the single most important factor that would have altered the rural areas and lifted the peasant from poverty. Both of them were merely anti-American.

And finally, we are poor because we have lost our ethical moorings. We condone cronyism and corruption and we don’t ostracize or punish the crooks in our midst. Both cronyism and corruption are wasteful but we allow their practice because our loyalty is to family or friend, not to the larger good.

We can tackle our poverty in two very distinct ways. The first choice: a nationalist revolution, a continuation of the revolution in 1896. But even before we can use violence to change inequities in our society, we must first have a profound change in our way of thinking, in our culture. My regret about EDSA is that change would have been possible then with a minimum of bloodshed. In fact, a revolution may not be bloody at all if something like EDSA would present itself again. Or a dictator unlike Marcos.

The second is through education, perhaps a longer and more complex process. The only problem is that it may take so long and by the time conditions have changed, we may be back where we were, caught up with this tremendous population explosion which the Catholic Church exacerbates in its conformity with doctrinal purity.We are faced with a growing compulsion to violence, but even if the communists won, they will rule as badly because they will be hostage to the same obstructions in our culture, the barkada, the vaulting egos that sundered the revolution in 1896, the Huk revolt in 1949-53.

To repeat, neither education nor revolution can succeed if we do not internalize new attitudes, new ways of thinking. Let us go back to basics and remember those American slogans: A Ford in every garage. A chicken in every pot. Money is like fertilizer: to do any good it must be spread around.Some Filipinos, taunted wherever they are, are shamed to admit they are Filipinos. I have, myself, been embarrassed to explain, for instance, why Imelda, her children and the Marcos cronies are back, and in positions of power. Are there redeeming features in our country that we can be proud of? Of course, lots of them. When people say, for instance, that our corruption will never be banished, just remember that Arsenio Lacson as mayor of Manila and Ramon Magsaysay as president brought a clean government.We do not have the classical arts that brought Hinduism and Buddhism to continental and archipelagic Southeast Asia, but our artists have now ranged the world, showing what we have done with Western art forms, enriched with our own ethnic traditions. Our professionals, not just our domestics, are all over, showing how accomplished a people we are!

Look at our history. We are the first in Asia to rise against Western colonialism, the first to establish a republic. Recall the Battle of Tirad Pass and glory in the heroism of Gregorio del Pilar and the 48 Filipinos who died but stopped the Texas Rangers from capturing the president of that First Republic. Its equivalent in ancient history is the Battle of Thermopylae where the Spartans and their king Leonidas, died to a man, defending the pass against the invading Persians. Rizal — what nation on earth has produced a man like him? At 35, he was a novelist, a poet, an anthropologist, a sculptor, a medical doctor, a teacher and martyr.We are now 80 million and in another two decades we will pass the 100 million mark.

Eighty million — that is a mass market in any language, a mass market that should absorb our increased production in goods and services - a mass market which any entrepreneur can hope to exploit, like the proverbial oil for the lamps of China.

Japan was only 70 million when it had confidence enough and the wherewithal to challenge the United States and almost won. It is the same confidence that enabled Japan to flourish from the rubble of defeat in World War II.

I am not looking for a foreign power for us to challenge. But we have a real and insidious enemy that we must vanquish, and this enemy is worse than the intransigence of any foreign power. We are our own enemy. And we must have the courage, the will, to change ourselves.

F. Sionil Jose, whose works have been published in 24 languages, is also a bookseller, editor, publisher and founding president of the the PhilippinesÕ PEN Center. The foregoing is an excerpt from a speech delivered by Mr. Jose in Manila, Philippines.

Excerpt from F. Sionil Jose's novel "Tree"

I sometimes pass by Rosales and see that so little has changed. The people are the same, victims of their own circumstances as Old David, Angel, Ludovico, and even Father had all been. God, should I think and feel, or should I just plod on and forget? I know in the depths of me that I'll always remember, and I am not as tough as they were. Nor do I have the humor and the zest to cope as Tio Marcelo did, looking at what I see not as an apocalypse but as revelation; as he said once, paraphrasing a Spanish poet, he was born on a day that God was roaring drunk.

I think that I was born on a day God was fast asleep. And whatever happened after my birth was nothing but dreamless ignorance. But there was a waking that traumatized, a waking that also trivialized, because in it, the insolence and the nastiness of human nature became commonplace and I grew up taking all these as inevitable. In the end, the satisfaction that all of us seek, it seems, can come only from our discovering that we really have molded our lives into whatever we want them to be. In my failure to do this, I could have taken the easy way out, but I have always been too much of a coward to covet my illusions rather than dispel them.

I continue, for instance, to hope that there is reward in virtue, that those who pursue it should do so because it pleases them. This then becomes a very personal form of ethics, or belief, premised on pleasure. I would require no high-sounding motivation, no philosophical explanation for the self, and its desires are animal, basic - the desire for food, for fornication. If this be the case, then we could very well do away with the church, with all those institutions that pretend to hammer into human being attributes that would make him inherit God's vestments, if not His kingdom.

But what kind of man is he who will suffer for truth, for justice, when all the world knows that it is the evil and the grasping who succeed, who flourish, whose tables are laden, whose houses are palaces? Surely he who sacrifices for what is just is not of the common breed or of an earthly shape. Surely there must be something in him that should make us beware, for since he is dogged and stubborn as compared with the submissive many, he will question not just the pronouncements of leaders but the leaders themselves. He may even opt for the more demanding decision, the more difficult courses of action. In the end, we may see him not just as selfless but as the epitome of that very man whom autocrats would like to have on their side, for this man has no fear of heights, of gross temptations, and of death itself.

Alas, I cannot be this man, although sometimes I aspire to be like him. I am too much a creature of comfort, a victim of my past. Around me the largesse of corruption rises as titles of vaunted power, and I am often in the ranks of princes, smelling the perfume of their office. I glide in the dank, nocturnal caverns that are their mansions and gorge on their sumptuous food, and I love it all, envy them even for the ease with which they live without remorse, without regret even though they know ( I suspect they do) that to get to this lofty status, they had to butcher - perhaps not with their own hands - their own hapless countrymen.

Today I see young men packed off to a war that's neither their making nor their choice, and I recall Angel, who is perhaps long dead, joining the Army not because he was a patriot but because there was no other way. So it has not changed really, how in another war in another time, young men have died believing that it was their duty to defend these blighted islands. It may well be, but the politicians and the generals - they live as weeds always will - accumulating wealth and enjoying the land the young have died to defend. This is how it was, and this is how it will be.

Who was Don Vicente,after all? I should not be angered then, when men in the highest places, sworn to serve this country as public servants, end up as millionaires in Porbes Park, while using the people's money in the name of beauty, the public good, and all those shallow shibboleths about discipline and nationalism that we have come to hear incessantly. I should not shudder anymore in disgust or contempt when the most powerful people in the land use the public coffers for their foreign shopping trips or build ghastly fascist monuments in the name of culture or of the Filipino spirit. I see artists - even those who cannot draw a hand or a face - pass themselves off as modernists and demand thousands of pesos for their work, which, of course, equally phony art patrons willingly give. And I remember Tio Marcelo - how he did not hesitate to paint calesas and, in his later years, even jeepneys, so that his work would be seen and used, and not be a miser's gain in some living room to be viewed by people who may not know what art is. I hear politicians belching the same old cliches, and I remember Tio Doro and how he spent his own money for his candidacy and how he had bowed to the demands of change. When I see justice sold to the highest bidder I remember Tio Baldo and how he lost. So honesty, then, and service are rewarded by banishment, and people sell themselves without so much ado because they have no beliefs - only a price.

I would like to see all this as a big joke that is being played upon us, but I have seen what was wrought in the past - the men who were destroyed without being lifted from the dung heap of poverty, without recourse to justice.

But like my father, I have not done anything. I could not, because I am me, because I died long ago.

Who, then, lives? Who, then, triumphs when all others have succumbed? The balete tree - it is there for always, tall and leafy and majestic. In the beginning, it sprang from the earth as vines coiled around a sapling. The vines strangled the young tree they had embraced. They multiplied, fattened, and grew, became the sturdy trunk, the branches spread out to catch the sun. And beneath this tree, nothing grows!

I think that I was born on a day God was fast asleep. And whatever happened after my birth was nothing but dreamless ignorance. But there was a waking that traumatized, a waking that also trivialized, because in it, the insolence and the nastiness of human nature became commonplace and I grew up taking all these as inevitable. In the end, the satisfaction that all of us seek, it seems, can come only from our discovering that we really have molded our lives into whatever we want them to be. In my failure to do this, I could have taken the easy way out, but I have always been too much of a coward to covet my illusions rather than dispel them.

I continue, for instance, to hope that there is reward in virtue, that those who pursue it should do so because it pleases them. This then becomes a very personal form of ethics, or belief, premised on pleasure. I would require no high-sounding motivation, no philosophical explanation for the self, and its desires are animal, basic - the desire for food, for fornication. If this be the case, then we could very well do away with the church, with all those institutions that pretend to hammer into human being attributes that would make him inherit God's vestments, if not His kingdom.

But what kind of man is he who will suffer for truth, for justice, when all the world knows that it is the evil and the grasping who succeed, who flourish, whose tables are laden, whose houses are palaces? Surely he who sacrifices for what is just is not of the common breed or of an earthly shape. Surely there must be something in him that should make us beware, for since he is dogged and stubborn as compared with the submissive many, he will question not just the pronouncements of leaders but the leaders themselves. He may even opt for the more demanding decision, the more difficult courses of action. In the end, we may see him not just as selfless but as the epitome of that very man whom autocrats would like to have on their side, for this man has no fear of heights, of gross temptations, and of death itself.

Alas, I cannot be this man, although sometimes I aspire to be like him. I am too much a creature of comfort, a victim of my past. Around me the largesse of corruption rises as titles of vaunted power, and I am often in the ranks of princes, smelling the perfume of their office. I glide in the dank, nocturnal caverns that are their mansions and gorge on their sumptuous food, and I love it all, envy them even for the ease with which they live without remorse, without regret even though they know ( I suspect they do) that to get to this lofty status, they had to butcher - perhaps not with their own hands - their own hapless countrymen.

Today I see young men packed off to a war that's neither their making nor their choice, and I recall Angel, who is perhaps long dead, joining the Army not because he was a patriot but because there was no other way. So it has not changed really, how in another war in another time, young men have died believing that it was their duty to defend these blighted islands. It may well be, but the politicians and the generals - they live as weeds always will - accumulating wealth and enjoying the land the young have died to defend. This is how it was, and this is how it will be.

Who was Don Vicente,after all? I should not be angered then, when men in the highest places, sworn to serve this country as public servants, end up as millionaires in Porbes Park, while using the people's money in the name of beauty, the public good, and all those shallow shibboleths about discipline and nationalism that we have come to hear incessantly. I should not shudder anymore in disgust or contempt when the most powerful people in the land use the public coffers for their foreign shopping trips or build ghastly fascist monuments in the name of culture or of the Filipino spirit. I see artists - even those who cannot draw a hand or a face - pass themselves off as modernists and demand thousands of pesos for their work, which, of course, equally phony art patrons willingly give. And I remember Tio Marcelo - how he did not hesitate to paint calesas and, in his later years, even jeepneys, so that his work would be seen and used, and not be a miser's gain in some living room to be viewed by people who may not know what art is. I hear politicians belching the same old cliches, and I remember Tio Doro and how he spent his own money for his candidacy and how he had bowed to the demands of change. When I see justice sold to the highest bidder I remember Tio Baldo and how he lost. So honesty, then, and service are rewarded by banishment, and people sell themselves without so much ado because they have no beliefs - only a price.

I would like to see all this as a big joke that is being played upon us, but I have seen what was wrought in the past - the men who were destroyed without being lifted from the dung heap of poverty, without recourse to justice.

But like my father, I have not done anything. I could not, because I am me, because I died long ago.

Who, then, lives? Who, then, triumphs when all others have succumbed? The balete tree - it is there for always, tall and leafy and majestic. In the beginning, it sprang from the earth as vines coiled around a sapling. The vines strangled the young tree they had embraced. They multiplied, fattened, and grew, became the sturdy trunk, the branches spread out to catch the sun. And beneath this tree, nothing grows!

Tuesday, May 8, 2007

Is work, child's play? Poverty in the Philippines: Case Study

Introduction

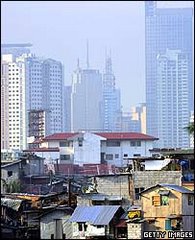

The Philippines, made up of a group of many islands, is a land of considerable beauty yet there are many contrasts. The country's wealth is not evenly distributed and a large percentage of the people live in poverty. In 1991, 40 percent of households lived in poverty. This has fallen to 32 percent in 1997 (World Bank, 2000). This still equates to millions of people living in urban slums or in rural areas that lack sanitation, safe water and other services that we take for granted. The challenge is to reduce poverty in light of a rapidly growing population.

Due to the poverty and lack of opportunities in rural areas, each year many people migrate to the cities looking for better economic opportunities. Most families are impoverished and children are often forced to earn an income. The types of jobs include selling items such as newspapers, cigarettes and lollies, or odd jobs such as car-washing, hauling or domestic work. Other possibilities include working in factories, construction sites, ports or small backyard industries, while some resort to scavenging or begging. The following are two examples of the lives of street and urban children in the Philippines.

Julie

Julie is a 10 year old girl who lives in Manila with her family. Julie's father is unemployed and her mother sells flowers in clubs near their home. Being the youngest of six children in her family, she has always accompanied her mother selling flowers from 10pm till 5am. Julie has been exposed to this lifestyle since she was five years old. Living in poverty has forced Julie to resort to the same job of selling flowers and key chains like her mother. Julie is exposed to drunks and street fighting as she sells her goods on the streets during the night.

Evelyn

Evelyn and her family migrated to Manila from the island of Samar when she was six years old. Evelyn, being the third of six children, came with her parents to Manila looking for better economic opportunities. Her father has irregular work as a jeepney driver while her mother is a market vendor. Evelyn and her older siblings were forced to work due to poverty and her parents unstable income.

Living conditions

Each year more people migrate from rural areas to the cities looking for better economic opportunities. Families come hoping that they can find a better lifestyle. Most have low education levels and lack marketable skills. Consequently they find it difficult to find ongoing stable employment. As a result they usually end up living in blighted areas.

Families rely on makeshift housing.

Under bridges, beside rivers, adjacent to landfills and near railways are just some examples of sites where these poverty stricken families may reside when they first come to the cities. Houses may be made from cloth, cardboard, corrugated iron, scrap wood, boxes, tarpaulins and rope. Living conditions are usually very poor, the areas are overcrowded, shelter is temporary and insubstantial and there can be a lack of basis needs such as water and sanitation. Access to health services is usually very poor or non-existent.

Impact on health

Children working on the streets are exposed to many hazards. Children who spend many hours working on the street are more susceptible to respiratory infections, pneumonia and other illnesses, and face a high risk of injury or death from motor vehicles. They can be used as accessories in drug deals, robberies, swindling and extortion. Some are even forced into child prostitution or other criminal activities.

Education

Street children often face difficulties in gaining an education and leaving the streets for the following reasons: they have limited access to quality education available in the areas where they live and work; irregular or low family incomes cannot cover the costs of school enrolment, uniforms and school projects; and

once enrolled in school, a high proportion of these children are forced to drop out, especially as school expenses rise in later years.

In the long term there is little chance of these children gaining meaningful employment, leaving the streets and breaking the cycle.

The Street and Urban Working Children Project

The Philippines' Government targeted street children and their parents as a vulnerable group that needed greater attention. In 1994 the Department of Interior and Local Government, with funding assistance from the Australian Government's overseas aid program, embarked on a five year project called The Street Children Nutrition and Education Project. Today this project continues as the Street and Urban Working Children Project.

The target group for this project are street and urban working children and their families. They are defined as: children aged 5 to 17 years old; children of urban impoverished families who spend a significant amount of time on the streets, usually not protected, supervised or cared for by responsible adults; those who have adopted the streets for their living and/ or source of livelihood; those who are street/community based and working, either in or out of school; those who have already been taken away from the streets but still need continued rehabilitation and care.

It should be noted that the vast majority of street and urban working children do live at home with a family, however the time they spend with the family may be minimal.

Project strategies

It is 7am and the non government organisation (NGO) bus pulls up in one of the poorer neighbourhoods in Manila. They load up the bus with children to take to the Old Fortress for the day. Arriving at the fortress there is a large grassed area at the front set up with tables and chairs where the children will spend the day. They will do basic schooling, literacy and numeracy and take part in value formation classes. At the end of the day each child will take home 1.5kg of rice as an incentive to return.

This is an example of how the project works in one area of the Philippines. In other areas children participate in vocational training including some income generating activities with money being passed on to the children. The aim is to increase their skills for future paid employment when they are older.

Parents of these children are also encouraged by the rice incentive to attend value formation classes for adults. The content of these classes includes the importance of health and education, caring and nourishment for their children, family values and morals, and the importance of keeping the children off the streets.

For the whole family the hope is with education and training, there will be improved access to economic opportunities and to social services. The schooling, vocational training and interaction with the NGO are all hoped to generate an increased level of participation in the community and ultimately to keep the children from working on the streets.

Another objective of the project is construct social development centres in each Local Government Unit (LGU) to effectively deliver social services now and help sustain the project after its termination.

Street Children Nutritional and Education Project

The rice has increased school attendance and improved the quality of participation at school.

The rice provided sufficient incentive for parents to regularly attend value formation training programs.

over 6,100 children reduced the time spent on the streets by 20% or more, and more than 2,600 children had been drawn from the streets completely.

What is life like today for Julie and Evelyn?

Julie

Julie is a bright and diligent student who was given the opportunity to be part of the project receiving rice, school supplies and a school scholarship. Julie dreams of becoming a nurse, "to help her family and the poor and sick people". She believes her dream will come true with the assistance from the project. The rice assistance and school scholarships have inspired her to study harder.

Evelyn

Evelyn now receives regular supplies of rice which has enabled her to concentrate more on her studies. The rice assistance has supplemented the families food, allowing money that would have been spent on rice to be spent on school projects. Evelyn is an active and diligent student who excels in her class and is determined to finish her schooling, and become a teacher to serve the poor and special children like her.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Top

© Commonwealth of Australia

The Philippines, made up of a group of many islands, is a land of considerable beauty yet there are many contrasts. The country's wealth is not evenly distributed and a large percentage of the people live in poverty. In 1991, 40 percent of households lived in poverty. This has fallen to 32 percent in 1997 (World Bank, 2000). This still equates to millions of people living in urban slums or in rural areas that lack sanitation, safe water and other services that we take for granted. The challenge is to reduce poverty in light of a rapidly growing population.

Due to the poverty and lack of opportunities in rural areas, each year many people migrate to the cities looking for better economic opportunities. Most families are impoverished and children are often forced to earn an income. The types of jobs include selling items such as newspapers, cigarettes and lollies, or odd jobs such as car-washing, hauling or domestic work. Other possibilities include working in factories, construction sites, ports or small backyard industries, while some resort to scavenging or begging. The following are two examples of the lives of street and urban children in the Philippines.

Julie

Julie is a 10 year old girl who lives in Manila with her family. Julie's father is unemployed and her mother sells flowers in clubs near their home. Being the youngest of six children in her family, she has always accompanied her mother selling flowers from 10pm till 5am. Julie has been exposed to this lifestyle since she was five years old. Living in poverty has forced Julie to resort to the same job of selling flowers and key chains like her mother. Julie is exposed to drunks and street fighting as she sells her goods on the streets during the night.

Evelyn

Evelyn and her family migrated to Manila from the island of Samar when she was six years old. Evelyn, being the third of six children, came with her parents to Manila looking for better economic opportunities. Her father has irregular work as a jeepney driver while her mother is a market vendor. Evelyn and her older siblings were forced to work due to poverty and her parents unstable income.

Living conditions

Each year more people migrate from rural areas to the cities looking for better economic opportunities. Families come hoping that they can find a better lifestyle. Most have low education levels and lack marketable skills. Consequently they find it difficult to find ongoing stable employment. As a result they usually end up living in blighted areas.

Families rely on makeshift housing.

Under bridges, beside rivers, adjacent to landfills and near railways are just some examples of sites where these poverty stricken families may reside when they first come to the cities. Houses may be made from cloth, cardboard, corrugated iron, scrap wood, boxes, tarpaulins and rope. Living conditions are usually very poor, the areas are overcrowded, shelter is temporary and insubstantial and there can be a lack of basis needs such as water and sanitation. Access to health services is usually very poor or non-existent.

Impact on health

Children working on the streets are exposed to many hazards. Children who spend many hours working on the street are more susceptible to respiratory infections, pneumonia and other illnesses, and face a high risk of injury or death from motor vehicles. They can be used as accessories in drug deals, robberies, swindling and extortion. Some are even forced into child prostitution or other criminal activities.

Education

Street children often face difficulties in gaining an education and leaving the streets for the following reasons: they have limited access to quality education available in the areas where they live and work; irregular or low family incomes cannot cover the costs of school enrolment, uniforms and school projects; and

once enrolled in school, a high proportion of these children are forced to drop out, especially as school expenses rise in later years.

In the long term there is little chance of these children gaining meaningful employment, leaving the streets and breaking the cycle.

The Street and Urban Working Children Project

The Philippines' Government targeted street children and their parents as a vulnerable group that needed greater attention. In 1994 the Department of Interior and Local Government, with funding assistance from the Australian Government's overseas aid program, embarked on a five year project called The Street Children Nutrition and Education Project. Today this project continues as the Street and Urban Working Children Project.

The target group for this project are street and urban working children and their families. They are defined as: children aged 5 to 17 years old; children of urban impoverished families who spend a significant amount of time on the streets, usually not protected, supervised or cared for by responsible adults; those who have adopted the streets for their living and/ or source of livelihood; those who are street/community based and working, either in or out of school; those who have already been taken away from the streets but still need continued rehabilitation and care.

It should be noted that the vast majority of street and urban working children do live at home with a family, however the time they spend with the family may be minimal.

Project strategies

It is 7am and the non government organisation (NGO) bus pulls up in one of the poorer neighbourhoods in Manila. They load up the bus with children to take to the Old Fortress for the day. Arriving at the fortress there is a large grassed area at the front set up with tables and chairs where the children will spend the day. They will do basic schooling, literacy and numeracy and take part in value formation classes. At the end of the day each child will take home 1.5kg of rice as an incentive to return.

This is an example of how the project works in one area of the Philippines. In other areas children participate in vocational training including some income generating activities with money being passed on to the children. The aim is to increase their skills for future paid employment when they are older.

Parents of these children are also encouraged by the rice incentive to attend value formation classes for adults. The content of these classes includes the importance of health and education, caring and nourishment for their children, family values and morals, and the importance of keeping the children off the streets.

For the whole family the hope is with education and training, there will be improved access to economic opportunities and to social services. The schooling, vocational training and interaction with the NGO are all hoped to generate an increased level of participation in the community and ultimately to keep the children from working on the streets.

Another objective of the project is construct social development centres in each Local Government Unit (LGU) to effectively deliver social services now and help sustain the project after its termination.

Street Children Nutritional and Education Project

The rice has increased school attendance and improved the quality of participation at school.

The rice provided sufficient incentive for parents to regularly attend value formation training programs.

over 6,100 children reduced the time spent on the streets by 20% or more, and more than 2,600 children had been drawn from the streets completely.

What is life like today for Julie and Evelyn?

Julie

Julie is a bright and diligent student who was given the opportunity to be part of the project receiving rice, school supplies and a school scholarship. Julie dreams of becoming a nurse, "to help her family and the poor and sick people". She believes her dream will come true with the assistance from the project. The rice assistance and school scholarships have inspired her to study harder.

Evelyn

Evelyn now receives regular supplies of rice which has enabled her to concentrate more on her studies. The rice assistance has supplemented the families food, allowing money that would have been spent on rice to be spent on school projects. Evelyn is an active and diligent student who excels in her class and is determined to finish her schooling, and become a teacher to serve the poor and special children like her.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Top

© Commonwealth of Australia

Wednesday, May 2, 2007

Opening Slots for Education Course and Technical Course (Welding)

SEND A SOUL TO SCHOOL MOVEMENT announces the opening of two slots for an EDUCATION COURSE (one from Talibon and another one from Jagna) at Blessed Trinity College (BTC Talibon) and 20 slots (10, Talibon and 10, Jagna)for a TECHNICAL COURSE (Welding) [TESDA Jagna].

QUALIFICATIONS

- a resident of Talibon or Jagna

- a Catholic of good standing

- a general average of at least 85% (80% for the technical course) in the fourth year high school card

- a high passing grade in the Blessed Trinity College Entrance Test; for the technical course, must pass the entrance examination of the Technical School chosen by the movement

- must come from a family whose income is not more than 30 thousand per annum

- must be single

- College age, that is, between 16-21

- for the technical course, between 21-30

GUIDELINES

- Application forms are available at the Most Holy Trinity Cathedral Parish office, Talibon and at St. Michael de Archangel Parish office, Jagna

- Deadline for filing of application is on Sunday, May 13, 2007. Application Forms may be submitted to the designated Parish offices or to Dr. Edsyl Hormachuelos’ dental clinic for the Talibon applicants. Upon submission of Forms the applicant must bring the following:

- Two 2” x 2” recent ID pictures

- medical certificate, good moral standing (from school last attended), and a cetificate of good family background (from the Barangay Captain)

- certification as to landholdings and occupation of parents

- a photocopy of Form 137 A

- a DSWD certificate as indigent

- a recommendation from the Parish Priest, if possible.

- Must take the Blessed Trinity College entrance examinations that will begin on May 16, 2007; for the technical course entrance exam, still has to be seen

- Those who will pass the Blessed Trinity College entrance examination will undergo an interview on Saturday, May 19, 2007 @ 9 am at Talibon Pension House, for Talibon applicants. For Jagna applicants at the Parish Rectory, on a similar date. The interview also includes the applicants for the technical course.

SCHOLARSHIP BENEFITS

- Tuition and miscellaneous privileges

- Provision for books and uniforms (school, P.E., CWTS)

- Board and lodging fees

- Monthly allowance

QUALIFICATIONS

- a resident of Talibon or Jagna

- a Catholic of good standing

- a general average of at least 85% (80% for the technical course) in the fourth year high school card

- a high passing grade in the Blessed Trinity College Entrance Test; for the technical course, must pass the entrance examination of the Technical School chosen by the movement

- must come from a family whose income is not more than 30 thousand per annum

- must be single

- College age, that is, between 16-21

- for the technical course, between 21-30

GUIDELINES

- Application forms are available at the Most Holy Trinity Cathedral Parish office, Talibon and at St. Michael de Archangel Parish office, Jagna

- Deadline for filing of application is on Sunday, May 13, 2007. Application Forms may be submitted to the designated Parish offices or to Dr. Edsyl Hormachuelos’ dental clinic for the Talibon applicants. Upon submission of Forms the applicant must bring the following:

- Two 2” x 2” recent ID pictures

- medical certificate, good moral standing (from school last attended), and a cetificate of good family background (from the Barangay Captain)

- certification as to landholdings and occupation of parents

- a photocopy of Form 137 A

- a DSWD certificate as indigent

- a recommendation from the Parish Priest, if possible.

- Must take the Blessed Trinity College entrance examinations that will begin on May 16, 2007; for the technical course entrance exam, still has to be seen

- Those who will pass the Blessed Trinity College entrance examination will undergo an interview on Saturday, May 19, 2007 @ 9 am at Talibon Pension House, for Talibon applicants. For Jagna applicants at the Parish Rectory, on a similar date. The interview also includes the applicants for the technical course.

SCHOLARSHIP BENEFITS

- Tuition and miscellaneous privileges

- Provision for books and uniforms (school, P.E., CWTS)

- Board and lodging fees

- Monthly allowance

Tuesday, May 1, 2007

POLICY FOR EDUCATIONAL PROGRAM

1.0 POLICY

The movement shall extend financial assistance to a deserving poor who wish to pursue College Education and Vocational Courses as defined hereunder.

2.0 SCOPE

This policy covers all the deserving poor of an organized chapter of the movement.

3.0 RESPONSIBILITY

3.1 Board of Trustees is responsible to:

3.1.1 See to it that the rules as outlined herein shall be strictly observed by those who wish to avail of the program.

3.1.2 Evaluate and approve the recommendations of changes and revisions from the chapter.

3.1.3 Strictly implement the approved budget in coordination with Finance.

3.2 Officers In a Respective Chapter

3.2.1 Information Committee

3.2.1.1 Provide proper and accurate information to those who seek clarification or who wish to inquire or get information concerning the program.

3.2.2 Screening Committee

3.2.2.1 Facilitate in the screening of applicants.

3.3.2.2 Approve the application of the deserving poor (scholar) in the chapter by ensuring that the course to which he/she will enroll in is somehow suitable to him/her.

3.2.3 Accounting/Finance is responsible to:

3.2.3.1 Follow up and receive donations from donors.

3.2.3.2 Monitor billing statements received from school and ensure timely payments.

3.3 The Scholar is responsible to:

3.3.1 Submit complete requirements (approved application form).

3.3.2 Submit study load after the enrolment and a copy of the course curriculum as needed.

3.3.3 Attend any required recollections or value formations.

3.3.4 Actively participate in any Church related activities especially during vacation time.

3.4 The Parents of the Scholars are responsible to:

3.4.1 Actively participate in any religious and socio-cultural activities.

3.4.2 Constantly support and follow up their children.

3.4.3 Attend any recollections and value formations organized by the movement for them.

3.4.4 Must join any Catholic religious organizations.

3.4.5 Shoulder any payment not included in the program.

4.0 DEFINITION OF TERMS

4.1 College Education – Any two-year, four or five-year degree.

4.2 Vocational Course – Any TESDA accredited courses or courses offered by Trade Schools.

4.3 Deserving poor

4.3.1 The poor who has gone through the movement’s examination and investigation.

4.3.2 A resident of a place where a chapter has been organized.

4.3.3 With parents not earning more than 30 thousand per annum.

4.3.4 A high school graduate or who had been through college but stopped due to financial problems.

4.3.5 Must be single.

4.3.6 College age, that is, between 16-21. For the technical course between 21-30.

4.4 Enrolment cost – 100% tuition fee and miscellaneous fees which to be paid by the movement once per semester only during enrolment period.

5.0 GUIDELINES

5.1 The Scholar can avail of one (1) degree course only, either College Education or Vocational under the movement’s program.

5.2 The schools where the scholars can enroll are the following Bohol Tertiary Schools, namely: HNU, CVSCAFT (any campus), STI, Informatics, Crystal e College, UB and Blessed Trinity College (Talibon).

5.3 Application Requirements

5.3.1 Certification as to landholdings and occupation of parents.

5.3.2 Medical certificate, good moral standing (from school last attended), and a certificate of good family background (from the Barangay Captain).

5.3.3 A DSWD certificate as indigent.

5.3.4 Recommendation from the Parish Priest, if possible.

5.3.5 A photocopy of Form 137 A

5.3.6 Must pass a set of tests and interviews.

5.4 Once accepted, here are the following requirements

5.4.1 The scholar is expected to get at least a 2.0 average grade or its equivalent grading system of all subject enrolled per semester or not less than 2.5 per subject. Failure to comply will be subjected to the movement’s evaluation.

5.4.2 Any failing grade shall automatically dismiss the scholar from the program.

5.4.3 Strictly no withdrawal of subjects unless dissolved.

5.4.4 The scholar is allowed to enroll in one (1) course only. Shifting to another course is not allowed.

5.5 Expenses exclusion/inclusion by the movement’s program.

5.5.1 Inclusion – Tuition fees, laboratory fees, registration, miscellaneous fees which includes library, medical/dental, athletics, guidance and testing, audio/visual, exam supplies, student development/human resource development (counseling, training), cultural fees, publications, modernization/upgrading for the school amenities. Board and lodging fees, living allowance, books (only required textbooks), provision for uniforms, retreats, field trips (half amount only), review and board examination fees.

5.5.2 Exclusion – School activities (parties, outings, acquaintance), school projects, graduation fees, graduation related expenses including diploma fees, thesis materials and oral defense (if any), alumni membership fees, homecoming assessment, toga, yearbook, class ring and such related expenses not hereto identified.

5.6 The scholar shall submit to the chapter officers his/her grades before the opening of the next enrolment otherwise he/she shall not be qualified to enroll for the next semester.

The movement shall extend financial assistance to a deserving poor who wish to pursue College Education and Vocational Courses as defined hereunder.

2.0 SCOPE

This policy covers all the deserving poor of an organized chapter of the movement.

3.0 RESPONSIBILITY

3.1 Board of Trustees is responsible to:

3.1.1 See to it that the rules as outlined herein shall be strictly observed by those who wish to avail of the program.

3.1.2 Evaluate and approve the recommendations of changes and revisions from the chapter.

3.1.3 Strictly implement the approved budget in coordination with Finance.

3.2 Officers In a Respective Chapter

3.2.1 Information Committee

3.2.1.1 Provide proper and accurate information to those who seek clarification or who wish to inquire or get information concerning the program.

3.2.2 Screening Committee

3.2.2.1 Facilitate in the screening of applicants.

3.3.2.2 Approve the application of the deserving poor (scholar) in the chapter by ensuring that the course to which he/she will enroll in is somehow suitable to him/her.

3.2.3 Accounting/Finance is responsible to:

3.2.3.1 Follow up and receive donations from donors.

3.2.3.2 Monitor billing statements received from school and ensure timely payments.

3.3 The Scholar is responsible to:

3.3.1 Submit complete requirements (approved application form).

3.3.2 Submit study load after the enrolment and a copy of the course curriculum as needed.

3.3.3 Attend any required recollections or value formations.

3.3.4 Actively participate in any Church related activities especially during vacation time.

3.4 The Parents of the Scholars are responsible to:

3.4.1 Actively participate in any religious and socio-cultural activities.

3.4.2 Constantly support and follow up their children.

3.4.3 Attend any recollections and value formations organized by the movement for them.

3.4.4 Must join any Catholic religious organizations.

3.4.5 Shoulder any payment not included in the program.

4.0 DEFINITION OF TERMS

4.1 College Education – Any two-year, four or five-year degree.

4.2 Vocational Course – Any TESDA accredited courses or courses offered by Trade Schools.

4.3 Deserving poor

4.3.1 The poor who has gone through the movement’s examination and investigation.

4.3.2 A resident of a place where a chapter has been organized.

4.3.3 With parents not earning more than 30 thousand per annum.

4.3.4 A high school graduate or who had been through college but stopped due to financial problems.

4.3.5 Must be single.

4.3.6 College age, that is, between 16-21. For the technical course between 21-30.

4.4 Enrolment cost – 100% tuition fee and miscellaneous fees which to be paid by the movement once per semester only during enrolment period.

5.0 GUIDELINES

5.1 The Scholar can avail of one (1) degree course only, either College Education or Vocational under the movement’s program.

5.2 The schools where the scholars can enroll are the following Bohol Tertiary Schools, namely: HNU, CVSCAFT (any campus), STI, Informatics, Crystal e College, UB and Blessed Trinity College (Talibon).

5.3 Application Requirements

5.3.1 Certification as to landholdings and occupation of parents.

5.3.2 Medical certificate, good moral standing (from school last attended), and a certificate of good family background (from the Barangay Captain).

5.3.3 A DSWD certificate as indigent.

5.3.4 Recommendation from the Parish Priest, if possible.

5.3.5 A photocopy of Form 137 A

5.3.6 Must pass a set of tests and interviews.

5.4 Once accepted, here are the following requirements

5.4.1 The scholar is expected to get at least a 2.0 average grade or its equivalent grading system of all subject enrolled per semester or not less than 2.5 per subject. Failure to comply will be subjected to the movement’s evaluation.

5.4.2 Any failing grade shall automatically dismiss the scholar from the program.

5.4.3 Strictly no withdrawal of subjects unless dissolved.

5.4.4 The scholar is allowed to enroll in one (1) course only. Shifting to another course is not allowed.

5.5 Expenses exclusion/inclusion by the movement’s program.

5.5.1 Inclusion – Tuition fees, laboratory fees, registration, miscellaneous fees which includes library, medical/dental, athletics, guidance and testing, audio/visual, exam supplies, student development/human resource development (counseling, training), cultural fees, publications, modernization/upgrading for the school amenities. Board and lodging fees, living allowance, books (only required textbooks), provision for uniforms, retreats, field trips (half amount only), review and board examination fees.

5.5.2 Exclusion – School activities (parties, outings, acquaintance), school projects, graduation fees, graduation related expenses including diploma fees, thesis materials and oral defense (if any), alumni membership fees, homecoming assessment, toga, yearbook, class ring and such related expenses not hereto identified.

5.6 The scholar shall submit to the chapter officers his/her grades before the opening of the next enrolment otherwise he/she shall not be qualified to enroll for the next semester.

GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF THE MOVEMENT

"Until one is committed, there is hesitancy, the chance to draw back, always ineffectiveness. Concerning all acts of initiative and creation, there is one elementary truth the ignorance of which kills countless ideas and splendid plans: the moment one definitely commits oneself, then … a whole stream of events issues from the decision, raising in one’s favor all manner of unforeseen incidents and meetings and material assistance which no man could have dreamed would have come his way. Whatever you can do, or dream you can do, begin it. Boldness has genius, power and magic in it. Begin it now."

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Official name: Send a Soul to School Movement

Acronym: SSoS

Also known as: A Thousand a Semester Movement

Introduction:

Poverty is a disturbing fact in our present society. In the Philippines, as defined by a recent study, the number of poor families already reaches to 4,022,695. In Bohol alone, the number is 65,953 (See “Poverty Incidence,” Philippine Daily Inquirer, Wednesday, June 14, 2006). These poor families in Bohol have an annual per capita of P10, 032.00, as the above study shows. Yet there is no need for any statistics to prove our point here. Just look at our surroundings, many people are poor.

The sad fact is that, these poor families can no longer afford to send their children to college. Education is supposed to be an inalienable right. As the Vatican II document Gravissimum Educationis puts it, “All men of whatever race, condition or age, in virtue of their dignity as human persons, have an inalienable right to education” (n. 1). Now these poor people have been deprived of this right. One cannot just turn one’s eyes away and close one’s ears to this problem. A concrete step must be done. One has to help these poor people. Recalling Jesus’ words, “Whenever you did this to these little ones who are my brothers and sisters, you did it to me” (Mt. 25:40). Thus this movement has been proposed to answer this great challenge before us.

Identity:

The movement is called SSoS that it may sound SSS. Education can always bring security. It may also sound SOS for education can always rescue one’s life from poverty. Hence, education is a key to a better life. Indeed, every person deserves such kind of life.

The movement is also known as A Thousand a Semester Movement, for every donor will donate one thousand per semester. This is significant for as the saying goes, “A thousand-mile begins with a single step.” The donor’s one thousand really makes a difference in the life of a poor person. This movement shall eventually become a foundation. This is a dream, and every dream begins by taking the first step.

Objectives of the movement:

Short term

1.To provide financial assistance to a deserving poor in whatever college/vocational course he or she is capable of.

2.To facilitate the employment of the scholars (graduates) through coordination with TESDA, and the Department of Labor and Employment.

3.To give spiritual and value formations to both scholars, with their parents, and donors or members of the movement.

Long Term

1.To revive the long lost culture of bayanihan.

2.To help eradicate poverty from our midst through education and formations.

Organization:

The movement shall begin in the towns of Talibon and Jagna in Bohol. A Board of Trustees shall be created. The board shall consist of nine (9) members, that is, four (4) from Talibon and four (4) from Jagna and with the founder as the other one. Aside from the Board, chapter officers shall be organized. Talibon shall become one chapter. The other is Jagna. Other towns are free to organize their own chapters, subject of course to the movement’s statute (still has to be formulated).

Membership:

The movement consists of the members of the Board of Trustees, the chapter officers, the donors, and the volunteers. Every donor automatically becomes a member of the movement. The members of the board of trustees, the chapter officers, and the volunteers may not be necessarily donors. The founder himself selectively chooses the members of the board of trustees and the chapter officers. The volunteers may be any individuals as long as they have good reputations in the community they live. Since the aim of the movement is holistic and not just financial assistance, the volunteers, with their time and talents, are of great help to the movement.

Works:

1.Decision-making

Decision-making shall belong to the board of trustees. Chapter officers shall then implement the decisions of the board.

2.Mechanics for funding

The major source of funding comes from the donation of the donors per semester. This shall be in a form of pledging. The donors are free to determine how many semesters they shall give. Fifty percent of a donor’s money shall go to the foundation’s account. The chapter shall use the other half for its own beneficiaries. Each chapter shall determine its beneficiaries. The foundation money shall be invested to generate more funds. Once the foundation’s money is already stable, it shall be used to subsidize a chapter’s need.

However, a donor can also donate more than one thousand. The one thousand for a semester may only be the minimum. Other amount exceeding one thousand for a semester will be appreciated. The donors do not only give money, but also have the task of looking for other donors.

The movement shall also need the help of any funding agency. Groups or other movements or NGO’s that are willing to help financially shall be deeply accepted.

3.The Poor Beneficiaries

Generally, the beneficiaries are the deserving poor. The board of trustees shall then specifically define this.

4. Value Formation

Financial assistance, as we have seen above, is not the only aim of the movement. Value formation to both members and scholars shall also be done. There may be annual retreats to both donors/members and scholars. The parents of the scholars shall also undergo value formations. The movement therefore shall demand a holistic approach.

Soon, a newsletter of the movement shall be produced. It shall contain the update of the movement and the written reflections of both selected members and scholars.

Time Frame of Establishment:

Organizing the movement shall begin this July 2006 until March of next year. Any donor shall initially give a minimum of one thousand pesos. Five hundred donors from both Talibon and Jagna shall be the partial targets of the movement. By June next school year (2007-2008), the movement shall begin sending a soul to school.

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Official name: Send a Soul to School Movement

Acronym: SSoS

Also known as: A Thousand a Semester Movement

Introduction:

Poverty is a disturbing fact in our present society. In the Philippines, as defined by a recent study, the number of poor families already reaches to 4,022,695. In Bohol alone, the number is 65,953 (See “Poverty Incidence,” Philippine Daily Inquirer, Wednesday, June 14, 2006). These poor families in Bohol have an annual per capita of P10, 032.00, as the above study shows. Yet there is no need for any statistics to prove our point here. Just look at our surroundings, many people are poor.

The sad fact is that, these poor families can no longer afford to send their children to college. Education is supposed to be an inalienable right. As the Vatican II document Gravissimum Educationis puts it, “All men of whatever race, condition or age, in virtue of their dignity as human persons, have an inalienable right to education” (n. 1). Now these poor people have been deprived of this right. One cannot just turn one’s eyes away and close one’s ears to this problem. A concrete step must be done. One has to help these poor people. Recalling Jesus’ words, “Whenever you did this to these little ones who are my brothers and sisters, you did it to me” (Mt. 25:40). Thus this movement has been proposed to answer this great challenge before us.

Identity:

The movement is called SSoS that it may sound SSS. Education can always bring security. It may also sound SOS for education can always rescue one’s life from poverty. Hence, education is a key to a better life. Indeed, every person deserves such kind of life.

The movement is also known as A Thousand a Semester Movement, for every donor will donate one thousand per semester. This is significant for as the saying goes, “A thousand-mile begins with a single step.” The donor’s one thousand really makes a difference in the life of a poor person. This movement shall eventually become a foundation. This is a dream, and every dream begins by taking the first step.

Objectives of the movement:

Short term

1.To provide financial assistance to a deserving poor in whatever college/vocational course he or she is capable of.

2.To facilitate the employment of the scholars (graduates) through coordination with TESDA, and the Department of Labor and Employment.

3.To give spiritual and value formations to both scholars, with their parents, and donors or members of the movement.

Long Term

1.To revive the long lost culture of bayanihan.

2.To help eradicate poverty from our midst through education and formations.

Organization:

The movement shall begin in the towns of Talibon and Jagna in Bohol. A Board of Trustees shall be created. The board shall consist of nine (9) members, that is, four (4) from Talibon and four (4) from Jagna and with the founder as the other one. Aside from the Board, chapter officers shall be organized. Talibon shall become one chapter. The other is Jagna. Other towns are free to organize their own chapters, subject of course to the movement’s statute (still has to be formulated).

Membership:

The movement consists of the members of the Board of Trustees, the chapter officers, the donors, and the volunteers. Every donor automatically becomes a member of the movement. The members of the board of trustees, the chapter officers, and the volunteers may not be necessarily donors. The founder himself selectively chooses the members of the board of trustees and the chapter officers. The volunteers may be any individuals as long as they have good reputations in the community they live. Since the aim of the movement is holistic and not just financial assistance, the volunteers, with their time and talents, are of great help to the movement.

Works:

1.Decision-making

Decision-making shall belong to the board of trustees. Chapter officers shall then implement the decisions of the board.

2.Mechanics for funding

The major source of funding comes from the donation of the donors per semester. This shall be in a form of pledging. The donors are free to determine how many semesters they shall give. Fifty percent of a donor’s money shall go to the foundation’s account. The chapter shall use the other half for its own beneficiaries. Each chapter shall determine its beneficiaries. The foundation money shall be invested to generate more funds. Once the foundation’s money is already stable, it shall be used to subsidize a chapter’s need.

However, a donor can also donate more than one thousand. The one thousand for a semester may only be the minimum. Other amount exceeding one thousand for a semester will be appreciated. The donors do not only give money, but also have the task of looking for other donors.

The movement shall also need the help of any funding agency. Groups or other movements or NGO’s that are willing to help financially shall be deeply accepted.

3.The Poor Beneficiaries

Generally, the beneficiaries are the deserving poor. The board of trustees shall then specifically define this.

4. Value Formation

Financial assistance, as we have seen above, is not the only aim of the movement. Value formation to both members and scholars shall also be done. There may be annual retreats to both donors/members and scholars. The parents of the scholars shall also undergo value formations. The movement therefore shall demand a holistic approach.

Soon, a newsletter of the movement shall be produced. It shall contain the update of the movement and the written reflections of both selected members and scholars.

Time Frame of Establishment:

Organizing the movement shall begin this July 2006 until March of next year. Any donor shall initially give a minimum of one thousand pesos. Five hundred donors from both Talibon and Jagna shall be the partial targets of the movement. By June next school year (2007-2008), the movement shall begin sending a soul to school.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)